An Embarrassing Oversight Helped Create Facebook's $167billion Mobile Advertising Business

Half-way through 2012, you’d have been forgiven for thinking that Facebook was doing a MySpace. In other words, Facebook was on a fast path to slow, painful decline.

Yahoo had just sued Facebook for patent infringement. Zuck - like Steve Jobs before him - had bet too early on the mobile web, and Facebook’s HTML5-powered apps were slow and buggy. Some argued that Zuck had overpaid for Instagram - $1billion for a 12 person company with no revenue, valued at half that amount a week before Facebook bought it.

The share price was tanking, having lost more than half its value just 3 months after going public. In Q3 2012 the company posted a net loss - it’s second quarter as a public company. And, though more than 50% of monthly active users visited Facebook on mobile, those users generated almost no advertising revenue.

If that wasn’t enough to finish Facebook off, advertisers weren’t exactly flocking to it, either.

Google’s search ads had earned a reputation as “the new standard” in the world of direct response advertising. They were easy to buy, easy to optimise, and it was easy enough to measure the impact of them. Google had tapped directly into a “standards-based” form of brand advertising, too. Adsense enabled advertisers to buy - through auction, at scale - display ads in standard IAB formats across hundreds of thousands of websites. Plug in your existing messages and creative, pick your audience, and go. SMBs loved it.

Exactly how many questions could be a in a Question ad?

In stark contrast, Facebook ads were almost impossible to buy. There were 27 different ad units to choose from. Facebook’s “Ads and Sponsored Stories Guide” was 45 pages long. To ensure maximum reach to Facebook’s audience on desktop and mobile, advertisers were required to create a gazillion images of various different dimensions and ratios. An infestation of bugs paused ad campaigns for no discernable reason (usually on Fridays, for entire weekends). Even worse, GM - one of the biggest brand advertisers on Facebook - publicly said Facebook ads didn’t work.

For a newly-listed company, with an advertising-based business model, the situation looked pretty bleak. Facebook was surely destined to join MySpace and Friendster in the dot-com deadpool.

Of course, as we now know, that never actually happened. Less than a year later, when Facebook announced Q2 2013 earnings, the stock shot up 21% in after hours trading after an earnings beat. Mobile accounted for 41% of revenue, up from 30% the quarter before. Facebook reported its first quarter with over 1 million active advertisers. Advertising revenue in “International” markets (EMEA, APAC, and LATAM) was doubling year-over-year. ARPU - a helpful metric to understand advertising auction demand - was growing faster than ever ($1.60 in Q2 2013, it’s $7.26 today).

How the heck did that happen? Simple answer: some good old platform thinking. And rationalizing.

When Facebook’s Ads Product team solicited feedback from marketers, it came thick and fast. It wasn’t great. Creating campaigns was equally intimidating, confusing and time consuming. Marketers were already investing time and money to create “organic” content on Facebook, like Page Posts. Adding 27 ad formats to the mix would create additional “work-work” for them.

To build empathy with the people they were serving, Ads PMs started adding the likes of David Ogilvy and Marshall McLuhan to their “must read” lists. And they started talking to the Ads API ecosystem more. Turns out the “work-work” problem was affecting developers, too. There were multiple ways to do similar things - or the same thing - through Facebook’s Marketing APIs. Internal confusion had been externalised to them. Wasting time re-inventing the wheel and implementing a constant barrage of new, different ad formats ate up their innovation budget.

A simpler approach was required. Marketers, developers, and Facebook were counting on it.

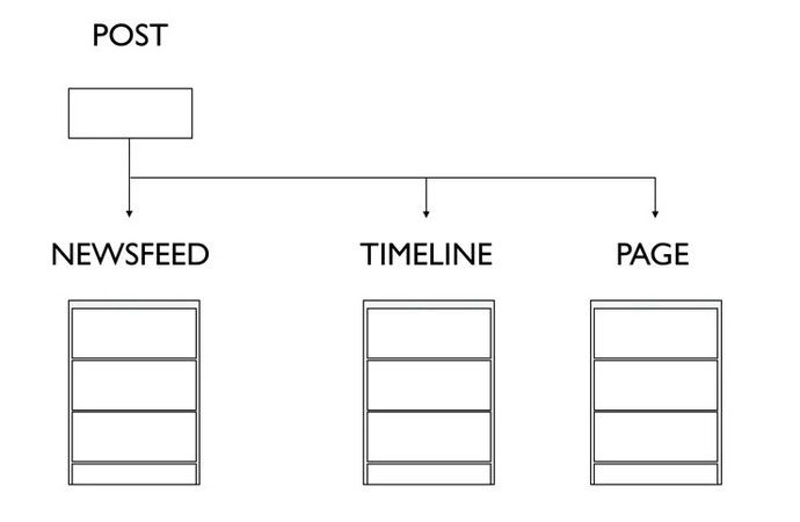

Paul Adams (now SVP Product at Intercom) was a Facebook Ads PM around then, and used simple diagrams like this to explain the “messages, containers, channels” idea.

Facebook’s Ads team quickly realised advertising on Facebook shouldn’t be all that different from advertising through any medium, old or new. It didn’t matter if was billboards, newspapers, magazines, leaflets, display ads, search ads, social ads, or emails, the basics were the same - marketers wanted to get messages in front of people, to drive a response.

The channels may vary, and containers within those channels may vary, but the messages and objectives were the same. And, of course, the best messages were those that started new relationships between businesses and customers.

This simple insight brought clarity to the conversation, and to the roadmap. Marketers were already creating “messages” on Facebook, after all - Page Posts. Instead of creating “ads” why not make it so that marketers could simply pay to get their existing messages in front of more people?

And, if these messages contained images - wasn’t that just the same thing as “ad creative?”

And, if these messages already appeared in users’ feeds, didn’t “feed” also mean “mobile feed”?

And, if marketers paid to promote these messages in “mobile feed,” aren’t they “mobile ads?”

The penny dropped.

For a self-proclaimed “platform company,” the approach to serving marketers and developers hadn’t been “platform-ey” at all. Lots of complexity, no consistency. Lots of distinct features were built, not rationalized capabilities. The feedback shared by marketers and developers was spot on - there were so many ways to do similar things - or the same thing - through every ads interface, not just Facebook’s APIs. An embarrassing oversight, but fixable with the right framework.

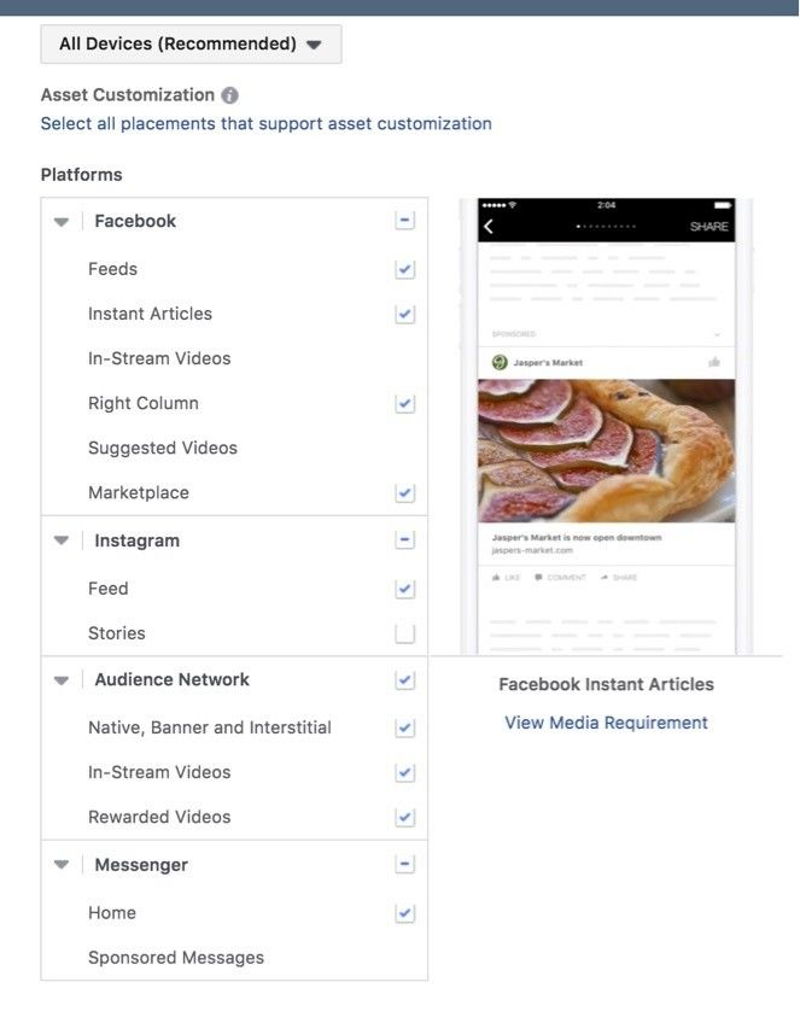

Changes came thick and fast. In June 2013, Fidji Simo penned - on behalf of the Ads Product team - “an update on Facebook Ads.” She used words like simplify, consistent, redundancies, streamline, and objectives to describe what was changing. Messages and images would gracefully degrade, depending on where they were delivered to people. The number of ad units would be reduced from 27 to fewer than half of that. Her final sentence summarised the changes well:

“We think these updates will make it easier for them (marketers) to do what they do best: reach the right groups of people with the right message and drive the results they care most about.”

Different containers, different channels, same message.

To say that Fidji was right is a mild understatement. Since 2012, marketers have invested over $167billion in mobile advertising through Facebook. In the 3rd quarter of 2019, mobile advertising represented 94% of Facebook’s overall advertising revenue. And, not all of that revenue came from the “big blue” Facebook app.

By simplifying the concept of a “message” reaching the “right groups of people” to “drive results,” advertisers could extend their advertising campaigns to Instagram and Facebook Audience Network with no additional effort. The messages they created would simply be presented in different types of containers, on different channels. When ads on Facebook Messenger appeared, the same messages created for Facebook and Instagram “gracefully degraded” to fit the containers on that new channel.

Even better, ads could quite literally be a new way to start a conversation with customers - through Facebook Messenger or WhatsApp. It was easy. SMBs loved it.

It didn’t stop there - life for developers improved, too. The process of integrating with Facebook’s Ads APIs became easier, and - by rationalizing across interfaces, including APIs - developers had more headspace and capacity to innovate. New Facebook Marketing Partners emerged with innovative solutions. Some, like Wix, created solutions to extend the reach of email marketing campaigns to Facebook. Others, like StitcherAds and Smartly.io enabled marketers to create digital circulars and data-fuelled ad creative. As of March 2019, almost $2 billion of Facebook’s annual revenue flows through Smartly.io - just one partner, based in Finland. There are more like them.

Facebook may have solved the “reach the right groups of people with the right message” problem well for advertisers within their own walled garden, but that doesn’t mean they’ve solved it for every business in the world. These days, the volume of inbound and outbound messages - emails, SMS, WhatsApp, and the rest - is ever increasing. A challenge for everyone, not just marketers.

Every team, in every business, wrestles with an infinite stream of inbound messages, and outbound messages that need to land in various apps and inboxes, on a myriad of devices, formatted in different ways. The number of “channels” is exploding, not consolidating. These days, TikTok is the new Tencent, Twilio is the new Telephone. WhatsApp and WeChat are the new browsers. Email and SMS are alive and well. But, just like Facebook advertising back in the day, managing all of this can be equally intimidating, confusing and time consuming.

The likes of Twilio - now a $40billion market cap company - are using terms like omni-channel, programmable conversations and conversational messaging to describe their capability to process and route inbound messages to the right teams, and route outbound messages to recipients on the channels they are most engaged with. Channels they ingest from and output to include email, SMS, voice, WhatsApp, Line, WeChat, Telegram, and many, many more.

If this all sounds familiar, it’s because it should be. “Graceful degradation” and orchestration of inbound and outbound messages across channels is uncannily similar to the “platform thinking” Facebook applied to create an entirely new multi-billion dollar mobile ads business.

This challenge, by itself, creates a market opportunity far greater than Facebook or Google’s market cap. These days, the opportunity can be sized in terms of $trillions, not $billions.

The next embarrasing oversight? Maybe it’s that messengers are really a new type of browser, or that voice, not video, is the next big mobile advertising opportunity. Only time will tell.